Thank you for your interest in RPhD! With my position at UNC, I haven’t been able to make the time I had hoped for blog writing. Perhaps some day I’ll pick this up again, but in the meantime, consider everything archived.

-Ben

Thank you for your interest in RPhD! With my position at UNC, I haven’t been able to make the time I had hoped for blog writing. Perhaps some day I’ll pick this up again, but in the meantime, consider everything archived.

-Ben

Like an army giving up ground in hopes of winning the war, Mylan today announced that it will soon be marketing a generic EpiPen. Unlike offering deeper discounts through the copay assistance program, this step may actually create some short term savings for the healthcare system. Mylan and CEO Heather Bresch should be recognized for not simply thumbing their nose at Congress and the press and maintaining their profit maximization strategy for EpiPen. Perhaps they learned a lesson from Martin Shkreli.

Called authorized generics, generic products marketed by brand name companies are surprisingly common. Oftentimes, these products are released alongside a competitor’s generic product as a way to reduce incentives for competitors to enter the market and for brand name manufacturers to make additional profit as product margins fall. Mylan’s strategy is unique in that there isn’t a generic equivalent available. Other very similar epinephrine autoinjectors are approved by the FDA, but they are not generically substitutable in most states.

Thanks, but…

There are several aspects of this news that give me reason to be critical about Mylan’s move. First, this is a blatant admission of profiteering. Selling the product for $600 when they could have sold it at a profit for $300 admits that Mylan was wringing as many dollars out of patients with severe allergies as possible.

Second, Mylan was probably going to do this anyways. Authorized generics are a common strategy for brand name product manufacturers, and the scrutiny over the price of EpiPen likely just resulted in Mylan releasing the authorized generic earlier than previously planned. As such, long term savings are likely minimal.

Third, the copay assistance program will not include the authorized generic. Therefore, it will still be cheaper for many patients to buy the brand name EpiPen, even though the total cost to the system will be larger. For an explanation, see my previous post on copay cards. Insurers and pharmacy benefits managers wishing to stop patients from using copay cards would have to eliminate EpiPen from their list of approved drugs, called a formulary. Formulary exclusions have become more common recently and are effective tools for reducing drug costs, but given Mylan’s success in marketing EpiPen, patients may be upset that they can’t get the brand name.

Finally, although the half-off, $300 price tag sounds like a relative bargain, it’s still 3 times more than what EpiPen used to cost. Additionally, a 50% discount isn’t nearly as deep as the 80% discount that one usually sees when generic competition enters the market. This discounted price also may discourage other generic manufacturers from bringing alternatives to market, thus maintaining a higher generic cost for longer.

Mylan will Remain Dominant

Mylan does deserve some acknowledgement for taking this interesting step to reduce the cost of EpiPen. Although my inner cynic wonders if the move is more in response to investor worries than patient needs, this will reduce the some of the short term cost of EpiPen. Expect to see patient confusion and frustration, however, as formularies tighten to eliminate coverage of brand name EpiPen.

In the long term, this move may also serve to lengthen the amount of time Mylan remains dominant in the epinephrine autoinjector market by discouraging generic competition. Until there is robust competition, don’t expect the price of Mylan’s EpiPen generic to fall further. There’s also Mylan’s direct selling strategy, and it is yet to be seen how much volume may flow through that alternative channel.

In the battle over EpiPen prices, Mylan is far from defeated.

Yesterday Mylan announced enhancements to its copay assistance program for EpiPens in response to Congressional and media scrutiny. These programs reduce the copay amount patients pay for EpiPen, but do they really reduce the price?

No. Despite what has been reported by the press, copay assistance programs don’t actually lower the price the healthcare system pays for drugs. If anything, copay assistance programs actually end up increasing drug prices.

Why Drug Companies Offer Copay Assistance Programs

Mylan’s announcement creates the illusion that it cares about patients using EpiPen. However, the expansion of their copay assistance program is false charity. Copay assistance programs reduce the headline grabbing copay amounts, but they do nothing to change that actual cost of the product to society. Copay assistance programs are also banned from use in all federal and some commercial insurance plans. All Mylan is really doing is taking steps to preserve its market share, or in words of Mylan’s CEO Heather Bresch, “ensuring that every patient that needs an EpiPen has an EpiPen.”

Patients may pay less but insurers end up paying more when discounted products are used more often and manufacturers raise the price to offset the losses from the assistance programs. Patients pay in the end via higher premiums. Mylan has yet to pledge that they won’t continue to raise the price of EpiPens. It is doubtless true that a more robust assistance program today will mean a more expensive product in the future.

How Copay Assistance Programs are like Eating Out on the Company Dime

The best analogy for how copay assistance programs increase spending this: Let’s say your boss takes you out to eat and offers to pay for the meal with the company credit card, but you have to pay for your own drinks. Knowing this, you choose the restaurant with the cheapest happy hour drink prices, even though the meals there are really expensive. If you were picking up the whole bill, you wouldn’t mind paying a bit more for beer if you can get the same meal at a cheaper price, but hey—the company’s paying, it doesn’t matter how much the food costs.

Your boss proceeds takes everyone in your department out for dinner and drinks with the same deal and they all go to the same restaurant because the drinks are cheapest. At the end of the year, your boss looks at the food budget and is shocked at how much has been spent. He/she decides to offset the meal cost by eliminating everyone’s year-end bonus. In the end, the cheap drinks lured you into over-spending on food and you eventually bore that cost through lower income.

In that way, copay cards give patients a false sense of affordability, but the increased cost to the insurer is eventually passed on to the patient in the form of higher premiums and deductibles. Mylan’s offering of discount cards does nothing to address the real problem—price gouging by drug companies with virtual monopolies.

What Can be Done to Decrease the Price of EpiPen?

Within the constraints of the current healthcare system, the only way to effectively reduce the price of EpiPen is to compete against it with alternative products. Fortunately, there are two products similar to EpiPen: Adrenaclick and its unbranded generic. Until more patients start talking to their doctors about alternatives, Mylan can continue to charge whatever it wants.

Perhaps because of Mylan’s effective marketing scheme, these alternatives have only a tiny share of the epinephrine auto-injector market. Absent competition, the next best option to push Mylan to lower the list price of EpiPen is scrutiny by Congress, media and consumers. Mylan’s stock price has fallen in response to this criticism—and when the entire purpose of a pricing scheme is to maximize shareholder value, this may eventually force Mylan to lower the EpiPen list price in an effort to calm investor worries and increase stock price. Capitalism FTW.

In short: Sure, but not very much, and don’t buy expensive test prep materials. NAPLEX studying can be a highly debated topic in the pharmacy community this time of year. When students ask me how much they should study, I often them that they shouldn’t study at all or that they should only study enough to make themselves comfortable with taking the exam.

Nearly Everyone Passes the NAPLEX

The biggest reason students shouldn’t study much for the NAPLEX is that nearly everyone passes on their first try. Across all schools of pharmacy, the average pass rate for the last 3 years is 94.2%. Pass rates do vary by schools, but nearly a third of all schools have 3-year average pass rates greater than 97%.

The NAPLEX is not designed to be hard. The NAPLEX is not to pharmacy what the Bar Exam is to law. The NAPLEX is a minimum competency exam wherein the board of pharmacy verifies that recent grads have enough knowledge not to harm to patients. If you’re a recent grad and concerned about passing, as long as your school has a reasonably high pass rate and you’re not at the academic bottom of your class, you’ll do fine.

Expensive Study Aids Aren’t Worth It

There are several study aids (ProntoPass, RxPrep, others) that promise to improve students’ scores on the NAPLEX. ProntoPass costs $399 and RxPrep costs between $149 and $788. This is a waste of money. It’s not surprising that students pass after using these aids—nearly everyone does. Passing is not a result of these study aids. Passing is a matter of probability.

I recommend students join APhA their P3 year and study using the free Complete Review for Pharmacy that comes with membership. This is the only reference that students need. If you’re a recent grad and not an APhA member, you can buy the book online for $72.95. It’s completely unnecessary to spend hundreds of dollars to study for a test that only 1 in 20 fail.

Take Time to Relax between Pharmacy School and Pharmacy Career

Beyond the idea that studying is inefficient and that commercial study aids are unnecessary and expensive, the time between PharmD graduation and starting a job/residency might be the longest stretch of time pharmacists will have without work when they’re not involuntarily unemployed out on maternity/paternity leave or retired.

For residents, the time between graduation and residency is a golden opportunity to decompress from the PharmD experience before ramping up for residency. If you got a residency, trust me—you’re going to pass the NAPLEX. I recall my wife’s residency roommates fretting all of May and June about passing the NAPLEX, wasting what would have otherwise been the perfect chance to relax and explore a new city. They later regretted not spending more time exploring their surroundings and decompressing before the stress of residency.

If You’re Going to Study Anything, Study for the MPJE

Years of therapeutics and rotations prepare students for the NAPLEX. If a student doesn’t learn the material there, they’re not going to learn it while cramming for 3 weeks after graduation. Students shouldn’t worry about the NAPLEX. It’s a minimum competency exam, and even with the updates coming for 2017, it still won’t be that hard for the average new graduate to pass the exam. If anything, students should focus on the MPJE. The typical pharmacy curriculum only has one class on pharmacy law, and students may be moving to a state they haven’t practiced in before.

If you’re a recent grad, take my advice: Relax, don’t worry, and try not to study too much.

Legislators are debating Iowa’s marijuana laws on the foundation of one basic question: Can a state expand access to medical marijuana while limiting recreational use?

Medical marijuana has been an active topic of debate by the Iowa Legislature for the better part of a decade. Democrats and Republicans have fought back and forth over whether a medical marijuana program expands access to marijuana for needy patients or encourages recreational use.

Is There Such a Thing as Medical Marijuana?

But there’s another question that must be addressed first before asking what expanding a medical marijuana program would accomplish: Does marijuana have medical use?

To explore the answer to this more fundamental question, it’s useful to understand the basics of pharmacology. Drugs work by binding to specific receptors in the body and the effect of a drug depends on the receptors to which it binds. Drugs are often grouped into classes based on the the receptors they bind to, but not all drugs in a class have the same effects on the body. For example, loperamide (the active ingredient in Imodium), hydrocodone, codeine and heroin all bind to the same types of opioid receptors in the body, but they each produce different effects.

Loperamide treats diarrhea by slowing down the GI system but it doesn’t get into the brain, so it doesn’t treat pain or cause addiction. Hydrocodone and codeine are both used for pain and cough, but codeine isn’t quite as potent as hydrocodone for treating pain yet works just as well for cough. Heroin causes all of these effects but is so prone to abuse that the Food and Drug Administration considers it a schedule 1 controlled substance—the most restrictive drug class possible. The FDA acknowledges the varying effects of opioids and regulates them accordingly.

The FDA doesn’t have the same sort of nuanced approach to marijuana. All natural forms of marijuana are considered—like heroin— schedule 1 controlled substances and, as such, the FDA does not consider them to have any medical use. Current research suggests, however, that the body has cannabinoid receptors in the same way it has opioid receptors. Cannabinoid receptors are located throughout the body and some of these receptors create the marijuana high while the effect of others is unknown.

Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the main component of marijuana that causes the marijuana high and there is one FDA-approved form of THC sold under the brand name Marinol. Marinol is indicated for anorexia in patients with AIDS and nausea and vomiting in patients with cancer, but the drug is rarely used and its efficacy has been questioned.

Cannabidiol (CBD), a cousin of THC, has been widely researched as a cannabinoid which doesn’t cause a high and has potential medical use. Check out PubMed and ClinicalTrials.gov for more information. The presence of cannabinoid receptors in tissues throughout the body suggests that it is not far-fetched to believe that CBD can be used to treat seizures, anxiety, psychosis, and other conditions unrelated to the more noticeable effects of smoking marijuana. The potential of cannabinoids in treating disease is a very active area of research and it is clear to me that marijuana does have some medical use.

The Medical Marijuana Debate in Iowa

Despite this, medical marijuana remains a divisive topic. Cannabidiol has been at the center of the medical marijuana debate in Iowa and many other states. The Iowa legislature passed a bill in 2014 to create a system that makes CBD oil accessible to Iowa residents—if they have intractable epilepsy, if nothing else has worked for them and a neurologist approves it. That’s an extremely narrow allowance for medical marijuana, but nonetheless, certain Iowans can currently legally possess a marijuana product for medical use.

The current Iowa law just barely creates access to medical marijuana. On the opposite end of the spectrum, California’s medical marijuana laws are so liberal that nearly anyone can purchase, possess and use marijuana. While Iowa is one of 17 states with limited distribution laws that allowing for some use of low THC marijuana products, California is joined by 22 other states with laws that variably allow for the production, sale and use of marijuana for medical purposes. The restrictions on use vary from states like Illinois, listing specific and mostly rare conditions that a person needs to have before being issued a card to purchase medical marijuana, to California’s lack of any specific medical conditions required before card issuance.

The progress on medical marijuana in Iowa is hampered by California’s deceptive medical marijuana program. Little doubt exists that the true intent of California’s program is to make recreational use of marijuana as legal as possible without actually legalizing it. For example, one of the bills that expanded California’s medical marijuana laws was named Senate Bill 420. Seriously. This differs greatly from Iowa’s attempts to put CBD oil specifically and only into the hands of patients who have cannabinoid-treatable conditions. It is clear to me that the purpose of Iowa’s medical marijuana program, and that of any state that only allows access to low-THC products, is to expand treatment options for patients, not to carve out legal safe harbors for recreational use.

The majority-Republican Iowa House refused last year to consider a Senate bill expanding Iowa’s medical marijuana program. The confusion between limited programs like Iowa’s and expansive programs like California’s contributes to the opposition. Both are called medical marijuana programs, yet California’s intent is to all-but-legalize the recreational use of pot. Therefore, it’s understandable that Republicans get nervous when considering a bill to expand Iowa’s program.

Momentum is building to expand Iowa’s medical marijuana program. Republicans seem to be warming to the idea of expanding access to medical marijuana, and a group of influential Des Moines businessmen recently wrote a letter to the Des Moines Register asking for the Iowa Legislature to pass legislation to create a more comprehensive medical marijuana program. In February, the House introduced a bipartisan bill (HF 2384) that would expand the use of cannabidiol oil to patients with cancer and multiple sclerosis, and allow for the manufacture, distribution and purchase of CBD oil in the state. Even if this bill doesn’t pass, it seems inevitable to me that some future bill will be successful in expanding Iowans’ access to medical marijuana.

What is the Future for Medical Marijuana?

The use of medical marijuana is expanding, but deriving cannabidiol and other medical cannabinoids from marijuana plants and creating 50 different regulatory bodies to oversee growth, production and distribution of medical marijuana is both inefficient and unsafe.

Many opioids are derived from the opium poppy, yet it would make no sense for a state to set up an intrastate poppy growing and distribution system. The only way to ensure that the opioids marketed in the US are used as safely and effectively as possible is first for pharmaceutical manufacturers to conduct large trials and for the FDA to make an objective decision on whether or not to approve a product. Then, physicians and other healthcare practitioners diagnose a need for and prescribe an opioid and pharmacists counsel on and dispense it.

In contrast, medical marijuana products are poorly researched, states have little experience regulating drug products, and nearly all systems of dispensing medical marijuana products lack healthcare practitioner oversight. Drug companies are currently investigating the use of CBD and I fully expect to see FDA approvals for cannabinoids in the next several years. Future FDA-approved products will diminish the need for state-run medical marijuana programs. It may very well be that in the future we look back on medical marijuana programs like Iowa’s as a historical curiosity.

Until that time comes, we have two types of medical marijuana programs: those allowing access for legitimate medical purposes and those allowing access essentially for recreational purposes. The confusion between these two programs is what makes medical marijuana a divisive issue. It’s right to make CBD oil available for children with seizures if we know it works: That is what a compassionate society does. Patients in need should have a way to access medical marijuana, and if the only way for now is to grow it in the state and dispense it through a non-pharmacy channel, so be it.

But masquerading recreational marijuana programs as medical marijuana programs makes beneficial health policy like what Iowa is pursuing more difficult to pass and implement. Let California follow Washington and Colorado’s lead and legalize marijuana for recreational use—that’s much more honest than calling their program medical marijuana and muddying the Iowa debate.

Note: A version of this blog post appeared on Little Village Magazine’s website and in its print edition. Thank you Lucy Morris for helping to shape this article and to the LV editing staff for trimming it for publication.

Confusion within pharmacy about biosimilars and interchangeable biologics is understandable. Pharmacists have decades of familiarity with biologic products but first biosimilar was only approved in 2015 and the FDA hasn’t yet written the rules to guide the application process for interchangeable biologics. One potentially confusing element related to these new types of products is the Purple Book. To understand the Purple Book, it is first necessary to understand the difference between biosimilars and interchangeable biologics.

What’s the Difference between Biosimilars and Interchangeable Biologics?

Both biosimilars and interchangeable biologics must be highly similar to an original, reference biologic product with no differences in safety and efficacy. This is analogous to the requirement that a generic small molecule drug must be bioequivalent to a reference small molecule drug.

The only difference between these two regulatory classes of medication is the interchangeability standards described in Section 351(k)(4) of the Public Health Service Act. If a product sponsor wishes to pursue interchangeability, it must submit additional information to the FDA that shows switching back and forth between the interchangeable product and the reference product doesn’t create safety and efficacy concerns. The FDA’s intention is that interchangeable products can be substituted at the pharmacy without the prescriber’s express authorization in the same way that pharmacists currently substitute generic products.

What Does the Purple Book Do?

The Purple Book does not decide which biologic are interchangeable. The FDA, through its authority to decide which drugs can be marketed in the US, rules on interchangeability pursuant to the requirements in Section 351(k)(4). The Purple Book only reports the pathway through which a product was approved and other information associated with the FDA’s approval decision. By reporting that a biosimilar product is not interchangeable, the Purple Book is not suggesting that the product can never be interchanged. Rather, it is simply stating that the product sponsor did not provide sufficient information to meet the FDA’s interchangeability requirements.

The Purple Book in no way impedes a hospital’s ability to create its own biologic product interchangeability list. In the same way that a hospital switches a patient from Novolin to Humulin because that’s the insulin the hospital chooses to keep on its formulary, the hospital can switch a patient from Neupogen to Zarxio because a pharmacy and therapeutics committee has determined that there is no problem switching between these products. Making this choice does not require creating a different Purple Book and the existence of the Purple Book does not impede a hospital’s ability to make this decision.

Why is it Important to Recognize the Purple Book as the Sole Authoritative Reference?

Drug manufacturers have lobbied hard to create confusion and mistrust within the biosimilar and interchangeable biologic classes of medication. They have attempted to insert language into states’ laws limiting a pharmacists’ authority to interchange products to only those that appear on a state list of interchangeable products. Requiring a redundant list would delay pharmacists’ authority to interchange biologic products because the list would need to be updated each time a new interchangeable biologic came to market.

States will ultimately decide on pharmacists’ authority to interchange biologic products. The purpose of the interchangeable biologic class is to allow pharmacists to interchange these products with reference biologics in the same way generics are substituted for brand name drugs. States can expand pharmacists’ authority to interchange products not deemed interchangeable by the FDA, but this would be through a statewide protocol, change to the practice act, or other similar mechanism to expand pharmacists’ authority.

Wrapping it All Up

The FDA, through its authority to decide what drug products can be sold in the US, can rule on product interchangeability. This information is copied over to the Purple Book to make it more accessible to patients, prescribers and pharmacists. If a state creates a redundant interchangeability list, this would only result in the restriction of pharmacists’ closely held product substitution authority. Hospitals disagreeing with the FDA’s determination on interchangeability can create a protocol, standing order, etc. within the confines of their state’s practice laws that would allow pharmacists to use therapeutic substitution to interchange biologic products. In no way does this conflict with the Purple Book.

Pharmacy must have a united voice on the development of the biosimilar and interchangeable biologic classes of medications. Drug manufacturers are pushing hard against the broad use of biosimilars and interchangeable biologics. These new classes hold exciting possibilities for pharmacists to further engage with the healthcare system in maximizing value drugs provide their patients. Pharmacists must recognize that the Purple Book is only a reflection of the FDA’s decisions when approving a product and that redundant lists of interchangeability only serve to limit the use of biosimilars and interchangeable biologics.

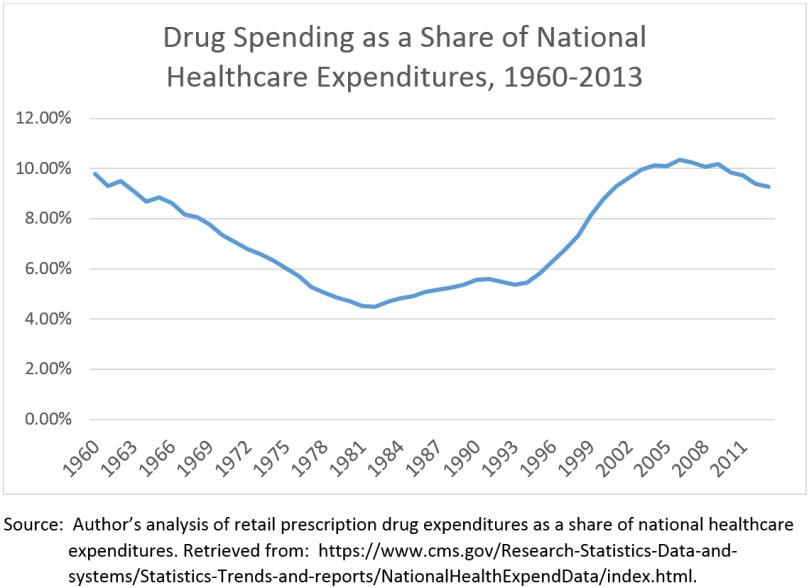

To combat the backlash against pharmaceutical prices, PhRMA has created a media campaign and website justifying the cost of drugs in the United States. They also released an infographic-filled report explaining why it is perfectly reasonable that the US spends far more on brand name medications than any other industrialized country. This blog post examines one specific claim PhRMA makes–that the healthcare system spends the same today on drugs that it did in 1960–and explores trends in drug spending.

PhRMA Myth: Drug spending as a share of total healthcare expenditures hasn’t changed since 1960.

Check out the YouTube video below and pay close attention to 0:19-0:39.

PhRMA is technically correct when it says that “spending on retail medicines accounts for the same percentage of healthcare spending today as in 1960.” What PhRMA doesn’t say, though, is that the 10% of national healthcare expenditures currently consumed by retail drug spending is twice as much as it was in 1980. Indeed, retail prescription drugs remained at less than 6% of national healthcare expenditures through 1995.

The text of the video and the infographic with decades passing by imply that spending has remained from 1960 through today. This suggestion is completely false. See the chart below for an analysis of how spending on retail prescriptions as a share of healthcare expenditures has changed over time.

Note the exponential rise in drug prices as a share of total healthcare expenditures during the mid 1990s to early 2000s. This was the heyday of pharmaceutical sales representatives selling expensive me-too drugs for cardiovascular conditions. Remember Dr. Jarvik? Of course you do. Incredibly successful marketing campaigns are at least partially to thank for this rise in spending.

The High Cost of Drugs is a Difficult Problem to Address

Prescription drug prices are a serious concern for the US healthcare system. Yes, it is true that optimal use of prescription drugs can reduce total healthcare spending, but when Sovaldi, even with a 50% discount, still costs more than a Mercedes C-Class, there is a problem.

Why is it that drugs cost so much in the US? The simplest reason is because they can be. There is little that stands in pharmaceutical manufacturers’ way of charging whatever they think the market can bear. Within the US, entities like the VA and Department of Defense that have tight formularies and cover large numbers of lives purchase at the lowest prices. The VA and DoD are not afraid to limit choices to save money.

Private industry can negotiate rebates with drug manufacturers, but evidence from Medicare Part D suggests that private insurers’ negotiations can’t beat mandatory rebates through Medicaid. Proposals to allow the federal government to negotiate on rebates within Medicare have been met with significant opposition from conservatives.

Unfortunately, the fragmented nature of the US healthcare system and cultural resistance to federal controls on drug prices means the issue of high prices is likely here to stay. Congress can wag fingers at drug manufacturers for charging exorbitant prices, but there isn’t much political willpower to do anything more than that.

Looking forward, prescription drug spending is expected to modestly outpace spending in other areas of healthcare over the next 10 years. Driving this trend are specialty biologic and small molecule products which are both life saving and extremely expensive. The new regulatory pathway for biosimilar and interchangeable biologic products does give some hope for competition to drive down prices of biologic products, but perceived differences between regulatory classes of biologics products may slow market penetration and limit competitiveness. Experience from Europe suggests that this may be the case.

A Look Forward

So where does this leave us? Despite what PhRMA says, spending on drugs has grown faster than other areas of healthcare since the 1980s and has only been at or around 10% of national healthcare expenditures since the mid 1990s. Spending on drugs is expected to continue to outpace other areas of healthcare spending for the next 10 years. The rhetoric from current presidential candidates provides some hope that whoever is in the White House in 2017 will address drug prices, but there still aren’t enough options for the federal government to “solve the problem.” Unfortunately, we are stuck with high drug prices for the foreseeable future.

Following the teenager’s trend, the FDA’s proposed policies on naming biologic products are totally random. As the healthcare industry prepares for the biosimilar era, the FDA is writing regulations and issuing draft guidance for industry to help healthcare practitioners differentiate between originator and follow on biologic products. This post explains biologic products, FDA proposed policy on biologic naming and concludes with my thoughts on the draft guidance.

What Are Biologics and Biosimilars?

For a quick refresher, there are three regulatory classes of biologics: originator biologics, biosimilars, and interchangeable biologics. Nearly all biologics are originator biologics. These are the brand names we’re familiar with—Neupogen, Enbrel, Humira, etc. Biosimilars have the same structure as originator biologics and receive approval through an abbreviated pathway specific to biologics which is similar but to the pathway for generic drug approval under Hatch-Waxman.

Biosimilars are “highly similar” to the reference biologic product and there can be no clinically meaningful differences between biosimilar and reference biologic. Interchangeable biologics follow the same pathway as biosimilars but go through additional steps to ensure that they can be substituted for reference, originator biologics without increasing the chance that the immune system reacts to the biologic entity (immunogenicity). Biosimilars will likely require small clinical trials to prove similarity; interchangeable biologics will likely require complicated cross-over clinical studies to prove switching between products doesn’t create immune reactions to the biologic product. For more information check out this informative PowerPoint from the FDA.

Importantly, federal law will provide pharmacists the legal authority to switch between interchangeable and reference biologics, but not between biosimilars and reference biologics. Switching between reference biologic and biosimilars is somewhat similar to situations like switching extended release diltiazem where different AB rated generics exist or switching between albuterol MDIs where multiple non-equivalent brands exist. The pharmacist could call a prescriber and switch the reference biologic to a biosimilar or from one biosimilar to another biosimilar with the same reference biologic, but there wouldn’t be clear authority to switch from biosimilar to biosimilar based on the prescription alone. Confused? The FDA created a Purple Book, analogous to the Orange Book, for the purpose of keeping this all straight.

So far there has only been one product approved through the biosimilar pathway—Zarxio (filgrastim-sndz) marketed by Sandoz. This is a biosimilar for the reference biologic Neupogen (filgrastim). Notice the funny suffix, -sndz, attached the nonproprietary name (AKA generic name) for Zarxio. This is what the FDA’s new guidance is about. Specifically, the new non-proprietary name for Zarxio would be filgrastim-bflm and the new name for Neupogen would be filgrastim-jcwp. The FDA would require manufacturers to market products under these names—the name on the Neupogen packaging would change.

Why is Biologic Naming a Concern and What is the FDA Doing About It?

This first biosimilar was given a suffix that clearly identifies it as 1) not an originator biologic and 2) manufactured by Sandoz. Neither one of these criteria necessarily says anything clinically relevant about the product’s efficacy, but differences could be perceived. Additionally, if an order/prescription was written for filgrastim, technically the pharmacist could not change that to filgrastim-sndz since the products are not interchangeable, even if the prescriber was indifferent to Zarxio vs. Neupogen when he/she wrote the order/prescription.

The FDA’s proposed solution to the problem is requiring all biologics, even those already approved for which a biosimilar is being developed, to be given a random 4-letter suffix that would differentiate between products but wouldn’t clearly indicate an originator product and wouldn’t indicate a manufacturer.

My Thoughts on a Better Naming System

The FDA’s concerns are valid, but I wonder if we’re missing an opportunity to encode more information in the suffix, the same way information is encoded in product names with standardized endings by class (e.g. –statin, -lol, -avir, etc.). An alphanumeric system, for example, with a random 3-letter code unique to each product-manufacturer pair with a single digit denoting originator, interchangeable or biosimilar would be a more effective way of communicating product status. The FDA could even use “4” for the originator, “7” for an interchangeable and “9” for a biosimilar to differentiate between biologic products but not clearly show which biologic the originator is.

Regardless, the use of a random 4-letter suffix seems to be missing out on a significant opportunity. The FDA is limited in the information that can be encoded in an NDC, and using a more purposeful suffix assignment process could allow more information to be encoded into a product name, making it easier for pharmacists, pharmacy technicians and prescribers to differentiate between originator, interchangeable and biosimilar products.

Opportunity to Voice Your Opinion

The FDA, like teenagers, seems to be overly fond of the idea of things being random. If you feel strongly and would like to voice your opinion on how this will impact your practice, the FDA will be accepting comments through October 27th, 2015.

Praluent (alirocumab, marketed by Regeneron and Sanofi Aventis) can claim three firsts: it’s the first FDA approved biologic for hypercholestolemia, the first in a class called PCSK9 inhibitors and the first biologic for prevention of chronic disease. PCSK9 inhibitors increase the clearance rate of LDL the blood and work incredibly well. In trials with patients already on maximally tolerated doses of statins, Praluent lowered cholesterol an additional 43-58% with relatively few side effects compared to placebo. These promising results make me very concerned.

Because Praluent doesn’t treat disease but reduces cholesterol in the hopes of preventing heart attacks, the pool of potential users is harder to define than biologics for, say, rheumatoid arthritis. Who is at risk for a heart attack and stroke? You are. I am. We all are. At what level of projected risk should we begin treatment? That’s a pretty complicated clinical question. Guidelines lend answers to the question, but as seen with the transition from JNC 7 to JNC 8, appropriate prevention—especially surrounding cholesterol—is still a relatively open question. This hard-to-define population makes the potential market for Praluent alarmingly large.

The Enormous Price of Innovation

There are 73.5 million people in the US with an LDL greater than 130. Even if only 1% of this population used Praluent, annual spending on this drug alone would exceed $8.5 billion. This calculation assumes a 20% discount off the annual WAC-based list price of $14,600 (73,500,000*.01*$14,600*(1-.2)). That’s enough to boost annual outpatient drug spending in the US (around $300 projected in 2016) by more than 2.5%. Heck, that’s more money spent on Praluent in one year than the entire annual GDP of the Bahamas.

Regeneron’s payments to physicians for services like consulting, education, travel and lodging and food/beverage exceeded $6 million in 2014. That excludes any payments to ancillary health professionals like nurse practitioners, physicians’ assistants and pharmacists. This number will undoubtedly grow as Regeneron markets Praluent to a PCSK9 inhibitor-naïve set of prescribers.

Unfortunately, community pharmacies will likely be left out of the distribution channel for Praluent and other PCSK9 inhibitors. Regeneron and Sanofi Aventis haven’t yet released their distribution channel strategy, but it is likely that the vast majority of patients who take Praluent will receive it through the mail from a specialty pharmacy or white bagging at a community pharmacy. Pharmacies will lose out on profit and the ability to maintain a complete record of their patients’ medication profile.

Important Caveats

There are a few silver linings which somewhat alleviate my concerns. First, Amgen has a rival PCSK9 inhibitor (Repatha, evolocumab) in the pipeline that’s already been approved in Europe and I expect it to be approved soon. Competition between Regeneron/Sanofi Aventis and Amgen will lead to significant rebates provided to third party insurers. Second, insurers will likely create strict prior authorization criteria to limit the number of people taking any PCSK9 inhibitor. Third, consolidation in the specialty pharmacy market increases the power of distributors to demand lower prices for Praluent, although this may only lead to greater specialty pharmacy profits and no real savings for the healthcare system.

Final Word

The bottom line is this: Praluent is effective, but does its effectiveness in reducing a surrogate marker of cardiovascular health justify the price society will pay for the drug? Praluent cost as much per day as a year’s supply of simvastatin costs at K-Mart. Is this 365-fold difference in price justified? If the US didn’t already spend 1 out of every 6 dollars on healthcare, I’d be more inclined to say yes.

While tying the idea of paying for value into the historical arc of clinical pharmacy, I came across an interesting thought: Was 1952 a low point for pharmacists’ involvement in patient care? Two historical items suggest the answer to this question may be, “Yes.”

1951 Durham-Humphrey Amendment

First, the 1951 Durham-Humphrey Amendment to the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FDCA), sponsored by two pharmacist-legislators, created distinct classes of pharmaceuticals—drugs that required a prescription and drugs that could be sold over-the-counter. Apparently, the primary focus of the amendment was not to establish this dichotomy but to make legal verbally transmitted prescriptions and prescription refills.[1] The federal enforcement mechanism was through the labeling provisions of the FDCA. If a pharmacist sold a prescription-only product without a prescription, that product would be considered to be misbranded and therefore in violation of the FDCA.

Prior to 1951, unless a drug had strong potential for abuse, there were no strong regulations on what products could or could not be sold without a prescription. Clearly, some regulation prohibiting unregulated sale of dangerous substances, is needed, but the Durham-Humphrey Amendment’s failure to establish a third class of behind-the-counter/pharmacist-only products is an issue the profession is still contending with. The Amendment failed to acknowledge pharmacists’ ability (insofar as it existed in 1951) to effectively oversee the use of medications that would perhaps be too dangerous for OTC sales but did not require assessment from a physician before use. First generation antihistamines are examples of products that would potentially fall into this category.

1952 Code of Ethics

The second historical item is the 1952 Code of Ethics.[2] This notorious document, published by the American Pharmaceutical Association, contains incredible quotes that that today seem beyond antiquated. In the second section of the code, “The Duties of the Pharmacist in his Relations to the Physician”, the Code of Ethics states that:

“[The pharmacist] should never discuss the therapeutic effect of a physician’s prescription with a patron nor disclose details of composition which the physician has withheld, suggesting to the patient that such details can be properly discussed with the prescriber only.”

The 1952 Code of Ethics illuminates a different era in pharmacy practice. The statement above clearly describes the patient-physician dyad, not the patient-pharmacist-physician triad of the current pharmaceutical care era. Indeed, it would be impossible to practice clinical pharmacy under the 1952 Code of Ethics.

Conclusion

The 1951 Durham-Humphrey Amendment missed an opportunity to put into law the pharmacist’s ability to make a difference in patient care through effective medication management. The 1952 Code of Ethics echoed the limitations on pharmacists’ abilities by restricting ethical practice to the dutiful and accurate dispensing of prescription products.

The 1960s witnessed encouragement by the APhA for pharmacists to develop a “patient orientation”, such as that of pharmacy pioneer Eugene White’s innovative office-type pharmacy.[3] The 1960s can be considered the origins of clinical pharmacy, which continued to develop through the 70s and 80s, resulting in the 1984 Nursing Home Reform Act’s mandate that pharmacists review medications for nursing home residents and OBRA 90’s requirement that pharmacists counsel Medicaid beneficiaries on prescriptions. The low point for pharmacists’ clinical practice may have been in 1952, and I am confident that with the current movement towards provider status, the high point is yet to come.

[1] Abood RR. Federal Regulations of Medications: Dispensing. In: Pharmacy Practice and the Law. 5th ed. 2008:113-164.

[2] Code of Ethics of the American Pharmaceutical Association. February, 1952.

[3] Sonnedecker G. Economic and Structural Development. In: Kremers and Urdang’s History of Pharmacy. 4th ed. American Institute of the History of Pharmacy; 1986:290-338.